China & the Silk Road

The Silk road (or Silk Roads) were established around 2,000 years ago during the Chinese Han dynasty (206BCE – 220CE). As the Han expanded into the Tarim Basin (modern day Xinjiang) they directly interfaced with the trade routes connecting the Mediterranean and Central Asia through the Persian Plateau. Archeological discoveries in Tarim Basin burial mounds attest to the broad trade that occurred during this time and include both Han and Roman coins, tablets with early Indic script as well as evidence of pile weaving, including woven fragments and carpet beater combs. It wasn’t only goods that traversed these networks, but also people and ideas. Buddhism arrived via the trade routes in the 1st century and would mingle with the native Daoism and Confucianism to create a distinctive tradition with a profound impact on the art and culture of China.

Domestic Rug Production

By the 13th century the Mongols would invade many lands along the Silk Road, including China where they launched the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368). Artisans were very important under the Yuan and many were recruited during wars of expansion, including Persian weavers. Textiles had such significance on trade that weavers were given special status. As artisans moved across the network weaving techniques were exchanged prompting many advances in textile design.

The Yuan established weaving settlements in the Tarim Basin, Inner Mongolia, and outside the new capital of Khanbaliq. As the Yuan dynasty gave way to the Ming Dynasty, Khanbaliq would be renamed Beijing. At it’s center, a nearly eight million square foot palace complex called the Forbidden City was built. The palace was outfitted with specially commissioned paintings, porcelain, sculptures and carpets woven locally in the imperial workshop.

The Manchu Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) arrived in the 17th century and brought a new appreciation and prestige to rug weaving. The carpets from this period are considered the finest of all Chinese classical production. The Manchus built many new Buddhist temples, endowing them with large annual appropriations, including a healthy portion set aside for rugs to cover their floors, pillars, seats and walls. It was during this time that most rug production moved to the Ningxia area. There was an abundance of wool in this region sufficient to meet the flourishing demand from the patronage of Buddhist monasteries as well as the aristocratic homes emulating the tastes of the court.

European Demand & the Rise of Tientsin

By the 18th century, European powers had built vast wealth through maritime trade and colonialism. Demand for Chinese products in the West was insatiable, whereas Chinese demand for European products was minimal, leaving the Europeans a large and concerning trade deficit. The British had an abundant supply of opium from their nearby colonies which they vigoruously pushed into the Chinese market to try to balance this deficit. Recreational use of Opium exploded throughout a society which had traditionally used the drug medicinally. The Chinese took action to outlaw Opium as the trade imbalance shifted and abuse soared. The attempts to limit and outlaw the trade ultimately lead to a series of wars. The European powers were victorious which allowed them to extract important trade concessions.

In 1858 the Treaty of Tientsin was signed, which opened the port city to foreign trade with Britain and France who would operate in exclusive zones of the city. By the end of the 19th century they were joined by Japan, Germany, Russia, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Belgium and the United States. Each zone or concession was self contained with distinctive attributes and architecture. Reminders of the period such as churches and European style villas survive to this day.

As trade expanded so would commercial production of rugs and other decorative objects for export from Beijing (Peking) and increasingly Tientsin. With increased production came modernization and the introduction of synthetic dyes and machine spun wool in the early 20th century.

Art Deco Carpets & The American Market

As the Qing Dynasty gave way to the Republic of China (1912-1949) and war took hold of Europe, the United States would become the largest market for Chinese carpets. The roaring twenties were a period of economic prosperity as well as a great social and cultural change in the United States. An American entreprenuer named Walter Nichols, and other enterprising though less famous producers, opened workshops in Tientsin to produce a new kind of carpet. The so-called “Nichols Chinese” or “Art Deco Chinese” would use innovative designs and modern production methods to become synonomous with the feeling of the era.

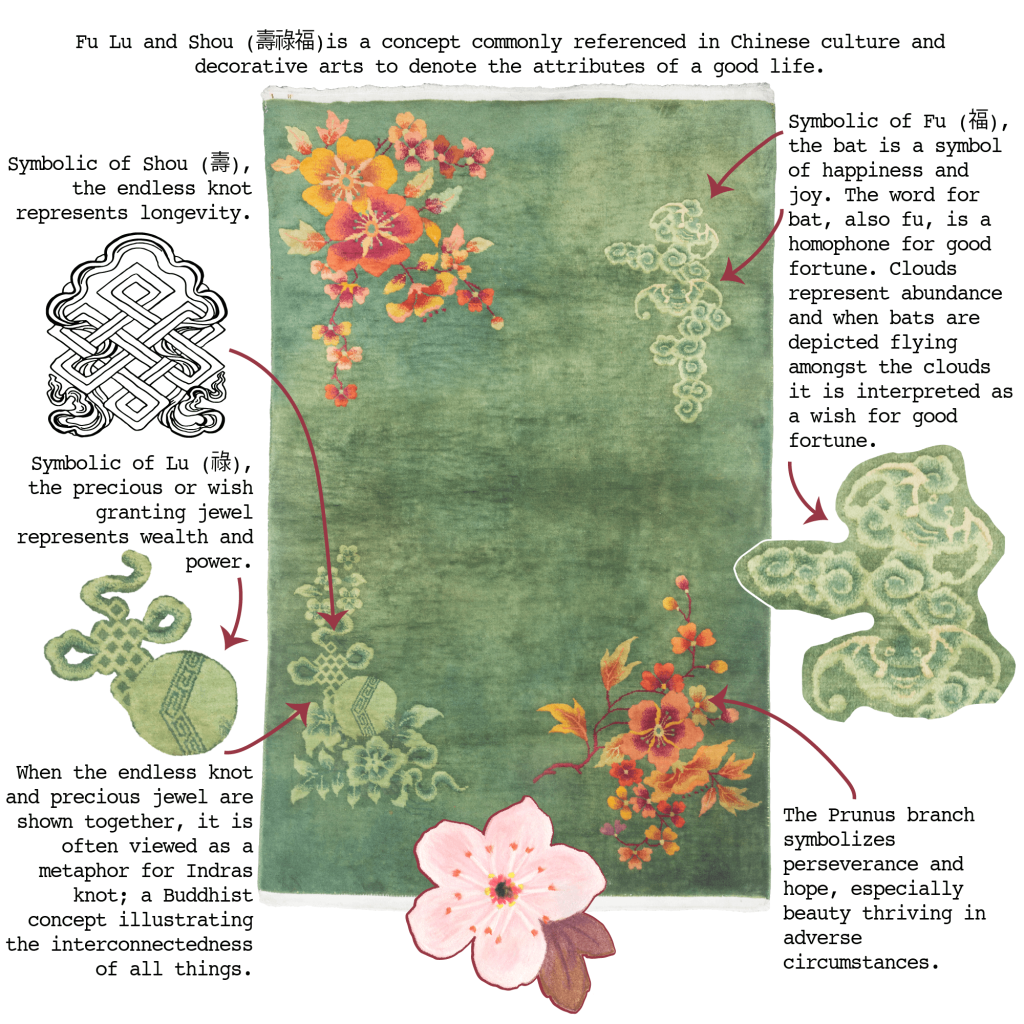

These carpets were a highly distinctive and succesful interplay of both Chinese and foreign market forces. Favoring the French Art Deco style they experimented with new dyes and contemporary Western art styles, which themselves had been influenced by the arts of China and Japan. These modern interpretations were often bright and borderless rugs with assymetric design. The usually naturalistic designs would reference or at times create new radical interpretations of traditional Chinese compositions. Buddhist and Doaist concepts and auspicious symbols were paired with spectacular and highly saturated colors that were often employed in unusual but gripping combinations.

Art Deco rugs would thrive throughout the 1920s and 30’s but the era would ultimately end as production came to an abrupt halt with the Japanese invasion of China and the onset of World War II.

We sourced our information from: Chinese Carpets by Charles Rostov & Jia Guanyan; Chinese and Exotic Rugs by Murray Eiland; Splendor of the Sons of Heaven: Imperial Chinese Carpets 1400-1750 by Hans Koenig & Michael Franses, Chinese Symbolism & Art Motifs by C.A.S Williams, Laszlo Montgomery’s The China History Podcast and Hali Magazine.