What is Ikat?

The word ‘ikat’ is derived from the Malay word mengikat, meaning ‘to tie’ or ‘to bind’. It describes the ancient textile technique as well as the finished fabric itself. This method of textile patterning involves tightly wrapping portions of vertical thread – the warp – with a resist material, before immersing it in a dye bath. The areas that are bound will resist the dye, and only the areas of the warp that are exposed to the dye bath will take the color. Through repeated tying and dyeing, more or less complex patterns can be created in a variety of colors. Once the pattern has been transferred onto the warp, it can be tied onto the loom and weaving can begin. The resulting textile will have a blurred or shimmery quality to it.

There are three types of ikat: warp-ikat, in which the ikat process is only done on the warp; weft-ikat, where the ikat is done on the horizontal threads (the weft); and double-ikat, when ikat is done on both the warp and the weft, and requires a highly advanced degree of technical skill to accomplish. The most commonly used fiber is cotton, followed by silk, which is more rarely used and only for certain types, like the double-ikat.

Traditionally, ikats were exclusively woven by noblewomen on simple backstrap looms, for they had the time to dedicate to long and complex weavings, but nowadays women of all social classes weave ikats. Women are in charge of everything from tying the warp threads to repeatedly immersing them in various dye baths, before finally weaving them into beautiful textiles. Traditionally, ikat employs few colors: indigo, the primary source for all shades of blue, is harvested and prepared by women according to specific rituals and practices, for it is cloaked in mystery and superstition. Red is obtained from the root of Morinda citrifolia (also known, among other terms, as great morinda, noni, or cheese fruit), and is called mengkudu or kombu. Indigo and mengkudu can also be combined together to create secondary colors. The undyed white cotton of the warp is also used as part of the traditional color palette. A lighter yellow or ochre color, derived from a variety of local plants, is painted on as a finishing touch once the ikat is complete.

As with many ancient techniques, we don’t know how or where ikat first appeared, although it is believed to have originated with the Dongson culture of Northern Vietnam during the Southeast Asian Bronze Age. Ikat was known in Java since at least the 9th century, and was likely diffused throughout Indonesia through trade links. Ikat is probably the most characteristic textile of Indonesia (warp-ikat weaving is practiced on almost every island on the archipelago), and East Sumba in particular is renowned for its striking figurative ikat weavings.

Island of Sumba

Sumba is an island that is part of the Lesser Sunda Islands in Indonesia, where textile traditions are very important, and imbue life from birth to death. Textiles are used for all kinds of ceremonial purposes, or to symbolize the wearer’s wealth and power. Sumbanese textile imagery combines influences from India, mainland Southeast Asia, and the Islamic world, as well as purely indigenous aesthetics, which refers to Sumba’s position along important trade and seafaring routes. Dutch colonial tastes also influenced textile imagery, and Dutch missionaries and colonists began collecting east Sumbanese textiles at the beginning of the 20th century. The commercialization and export trading of Sumbanese textiles began in the 1920s, which also coincided with the erosion of the aristocracy’s power, resulting in the relaxation of sumptuary laws. Until then, only the aristocracy, or maramba, could wear ikat woven in three colors (hinggi kombu), while commoners, or kabihu, could only wear ikat woven in two colors (hinggi kaworu). Nowadays men of all social classes wear hinggi kombu, though it is still mainly reserved for special occasions or ceremonies.

Hinggi Kombu

Of all the Sumbanese textile traditions, ikat is one of the most sophisticated. The coastal plains and river valleys of east Sumba are perfect for growing indigo, cotton, and morinda, the basic raw materials for hinggi kombu.

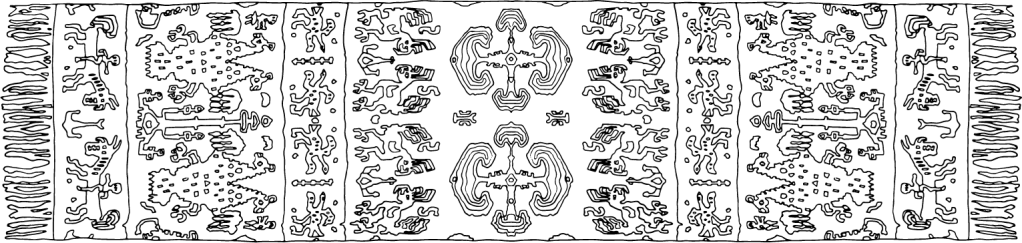

A hinggi is a man’s ceremonial mantle; kombu references the red mengkudu dye used. Hinggi are traditionally woven in pairs, to be worn around the hips and/or shoulders depending on the occasion. They are imbued with potent protective symbolism, related to Marapu, the practice of ancestor worship that is still practiced today in some rural communities.

Ikat imagery and symbols have specific meanings. For example, roosters and cockerels are associated with masculinity, heralding arrivals, and the wielding of vigilant power. Chickens symbolize protective, or ancestral power; those seeking information from the higher power of Marapu ancestors look for it in chicken entrails. Sumbanese nobility also adopted foreign motifs into their dress as a symbol of alliance with foreign powers. One prominent example was the lion coat of arms which was derived from the Dutch crest on the medals and flags given to the Sumbanese rulers by European traders for the Dutch East India Company.

Patterns that are hard to render in ikat are also especially prized in eastern Sumba, such as intricate curving forms or complex designs that require tight and precise binding of the warp threads. Also highly valued are deeply saturated colors, for the time and skill they require from the dyer from the dyer.

We sourced our information from: Textiles of Southeast Asia: Tradition, Trade and Transformation by Robert Maxwell; Traditional Indonesian Textiles by John Gillow; The World of Indonesian Textiles by Wanda Warming and Micheal Gaworski; Handwoven Textiles of South-East Asia by Sylvia Frasier-Lu; Between the Folds: Stories of Cloth, Lives, and Travels From Sumba by Jill Forshee; Hali Magazine