An Early History of the Qashqa’i People

Southwest Persia is both the historic homeland and the most fabled region of the Persian people. It was from here that Cyrus the Great would establish the Achaemenid Empire around 2,500 years ago. It would become the largest empire the world had seen up to that point and the ruins of its capital Persepolis still survive to this day as a UNESCO world heritage site.

Although successive empires would control the region, the forefathers of the peoples we refer to as Qashqa’i didn’t begin to enter the Persian plateau until roughly 1,000 years ago. It is believed that the Qashqa’i are descended from a branch of Oghuz Turks that had initially settled in Northwest Persia for several centuries before ultimately migrating south during the 16th century. In their folklore the Qashqa’i descend from the Turkic tribes that helped establish the Safavid Dynasty and migrated to southwest Persia at the invitation of Shah Ismail in order to protect the region from Portuguese incursions.

The Seasonal Migration

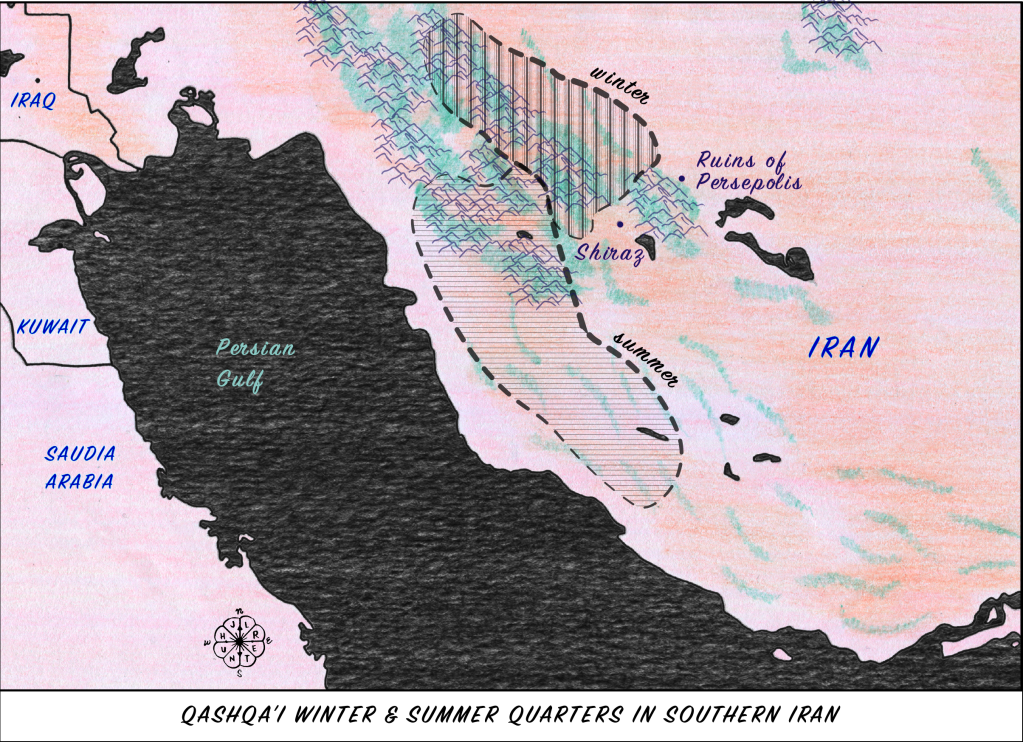

The Qashqa’i have a long tradition as pastoral nomads who follow a fixed migration moving from Summer to Winter quarters in the Zagros mountains each year. They are organized as tribes that have formed a symbiosis with the sheeps and goats which they raise and the pastures that provide their sustenance. It is a life for the animals that is defined not only the animals themselves but the bounty they provide. Both the flock and the weavings made from their wool represent the each families wealth, status and livelihood.

When a couple marries they receive an inheritance of a portion of the groom’s family’s sheep, goats, and pack animals with which to establish their own flock. From a young age a bride begins to make her dowry which traditionally included utilitarian objects like woven bags, cloths and other household items but might also contain ceremonial items like animal trappings for the bridal procession or fine rugs woven as gifts for the groom’s family. A woman’s status and prestige within the tribe is defined by her weaving skills. Many weavings are important for everyday life and can have multiple functions. Woven bags used during the migration are also utilized for storage in the tent during more sedentary times. Weaving is the primary way in which a woman can contribute to the family income as well as her main opportunity to express herself artistically.

The migration occurs twice a year spanning a few hundred miles and takes at least one month each time. Although the majority of their time is spent in a fixed location, the activities involved in the migration provide meanings for the cultural symbols, values and customs of the society. Most social interactions outside of the tribe occur during these journeys and it is the prime opportunity to trade weavings, wool and other goods commercially. Nomadic families present their best face while traveling. Women wear their finest clothes and their most colourful weavings are displayed on the outside of the pack animals.

Emergence & Decline

As the Qashqa’i established themselves in southwest Persia they maintained their distinct language (a Turkic dialect, most closely related to Azeri) and much of their nomadic heritage as they both conquered and blended with some of the other dominant cultures of the region, most prominently the Luri people. This is well represented in Qashqa’i weavings which while distinctive, display both marked Caucasian and Luri flavor among other influences.

Unable to exert their authority directly, the Qajar Dynasty (1789-1925) relied on various khans or tribal leaders to perform the functions of the state in their territories. By the 19th century the Qashqa’i had become quite powerful both politically and economically and were operating as an autonomous confederation of tribes. As a counterweight to the Qashqa’i the Qajars would combine five existing tribes into a confederation known as the Khamseh (literally – the five) in the early 1860s.

Following the first World War, the newly established Pahlavi dynasty set out to control the wealth and power that the Qashqa’i and other tribes had accumulated. Forced settlement of pastoral nomads was part of a larger strategy to centralize authority and modernize the state. As the Persian monarchy weakened with foreign occupation during the second World War, the Qashqa’i would resume their traditional migration and returned to autonomous governance. The monarchy would fall and a new leader democratically elected leader, Mohammad Mossadeq, would be actively supported by the Qashqa’i leadership. Mossadeq was soon overthrown by a CIA supported coup and the Shah reinstated. Most of the Qashqa’i leadership was exiled for their support of Mossadeq and as part of a modernization efforts all pasturelands were nationalized. Migration was highly restricted and placed under the control of the military.

After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, restrictions would loosen and a level of autonomy reestablished. By then, a large number of Qashqa’i had already completed the transition to either settled agriculture or urban life. Today, there are less than half a million Qashqa’i living in Persia and only a small percentage actively participate in pastoral nomadism. Yet the southwest of Persia remains one of the few places in the world where this seasonal migration still takes place at such scale. Tens of thousands of Qashqa’i and much larger numbers of livestock continue to make the ancestral journey together each year.

“All too often in the arts, for whatever reasons, the ‘era of Appreciation’ is delayed until after the ‘era of Creation’ has passed.” James Opie

We sourced our information from: kilim: The Complete Guide by Alastair Hull & José Luczyc-Wyhowska; Tribal Rugs: Treasures of the Black Tent by Brian W. MacDonald; Tribal Rugs: A Complete guide to Nomadic and Village Carpets by James Opie; The Qashqa’i Nomads of Persia by Mohammad Shahbazi and Hali Magazine